The poster of the exhibition organized in 2013, the 70th anniversary of the Russian Campaign

1941 The beginning of the Russian Campaign

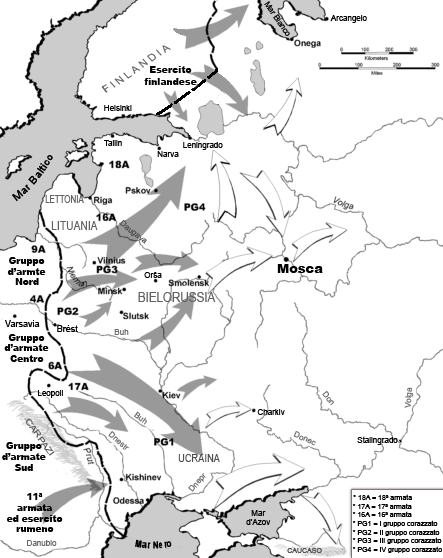

On June 22, 1941, Germany invaded the USSR. The reasons for the attack were both ideological and strategic. On the one hand they wanted to pursue the fight against communism and the conquest of the Living Space (Lebensraum) on the other Hitler was convinced that Stalin was plotting a surprise attack against Germany and with Operation Barbarossa he intended to anticipate it. In reality it wasn't like that. The offensive against the USSR was launched on a very broad front: from the polar circle to the Black Sea. There were three main directions: North with Leningrad as an objective, Center with Moscow as an objective, South with Kiev as an objective. The German army was large, but not big enough. It was therefore necessary to resort to the help of the allies: Romania, Hungary, Finland and even Slovakia sent expeditionary forces. Other countries such as Spain and Portugal allowed their citizens to serve as volunteers in the Wehrmacht, many anti-communist Soviet citizens were also recruited who formed entire divisions of the army and the Waffen-SS (Latvians, Estonians, Lithuanians, Ukrainians, Cossacks etc.).

Operation Barbarossa – June 1941Italy contributed almost immediately with the CSIR (Italian Expeditionary Force in Russia), made up of 3 divisions plus various Army Corps departments for a total of approximately 62,000 men, which arrived in southern Russia in August 1941. It was commanded by General Giovanni Messe, one of the best Italian commanders of the time. The CSIR gave a good performance, so much so that the Germans asked for more Italian troops to be sent. In May 1942 Mussolini decided to form a new Expeditionary Force, ARMIR, which became operational in July. There were 230,000 men in total divided into 3 Army Corps, one of which was Alpine, commanded by General Italo Gariboldi. The CSIR was renamed XXXV Army Corps and was incorporated into the ARMIR. In addition to the ground forces, an Air Corps of the Regia Aeronautica also operated in Russia (with fighter, reconnaissance and transport aircraft), and a naval contingent of the Regia Marina made up of MAS, midget submarines and other small units, which was sent to the Black Sea. achieved several successes against Soviet shipping.

Meanwhile, the advance of the Axis Forces in southern Russia had suffered a setback. The Soviets had managed to accumulate considerable reserves and, starting from August 1942, launch counter-offensives that had thrown the entire sector into crisis. The ARMIR, deployed between the Hungarian Army to the north and the Romanian Army to the south, stopped the attacks at the cost of heavy losses. Until November the situation remained almost unchanged, with Italian troops stationed on a 270 km front set up with defensive works similar to those of the Great War. On 19 November 1942 the Red Army launched a massive offensive aimed at encircling the German 6th Army engaged in Stalingrad. The action also led to the annihilation of the Romanian Army, deployed south-east of the ARMIR. In this way the Italians remained dangerously exposed to new possible enemy maneuvers.

On December 16th another Soviet offensive (Operation Little Saturn) was unleashed against the central sector of the Italian front. The first attack was repelled, but on December 17 the Russians used their armored troops and aviation, overwhelming the defenders and forcing them to retreat. The objective of the great Soviet maneuver was to join the two arms of a pincer, formed by powerful armored groups, behind the Italian-German-Romanian deployment. On 21 December the two Russian columns coming from the north and the east met at Degtevo, effectively closing the Italian XXXV Army Corps and the German XXIX Army Corps in an immense pocket. Almost without means of transport, forced to wander on foot in search of a way out, the ARMIR infantry divisions ended up largely annihilated, decimated by hunger, by a bitter cold, by the attacks of enemy armored columns and partisan units that acted behind them.

On January 12th, 1943 the Soviets launched the second phase of the offensive, overwhelming the Hungarian Army, deployed to the north of the Alpine Army Corps. The Alpine Army Corps remained closed in a pocket that also included the Vicenza division. The order to retreat from the Don was given only on 17 January, very late.

During the retreat, the Axis troops (in particular Italians but also Hungarians and Germans) marching westwards found their way blocked by large Soviet forces who had barricaded in the village of Nikolajevka. The unit that remained relatively intact and still capable of fighting was the Tridentine Alpine Division. With a desperate attack led by the division commander General Reverberi (MOVM), the Alpine troops managed to get the better of a much better equipped enemy, albeit at the price of serious losses. The Alpine troops succeeded in the miracle, even going so far as to take prisoners, capture fourteen cannons and reuse them against the Russians. There were countless acts of heroism, and many decorations for valor that were awarded; an epic battle, which cost the lives of many Alpine soldiers. Thus it was that around 20,000 men, including more than 7,000 wounded or frozen, managed to get out of the pocket and reach the friendly lines in Shebekino on 31 January. Of the 4 divisions only one, the Tridentina, had managed to remain overall intact, although heavily bled. Of the others, only a few thousand men managed to return, mostly stragglers.

With the substantial destruction of the ARMIR, Italian participation in the campaign on the Eastern Front effectively ended. Only a few smaller units remained operational, reporting directly to the Wehrmacht. The CSIR in the initial stages of the Russian campaign had over 1,600 dead, 5,300 wounded, more than 400 missing and over 3,600 frozen. Between July 30th 1942 and December 10th 1942 the ARMIR had 3,216 dead and missing and 5,734 wounded and frozen. As for the losses during the battle on the Don and the retreat, the official figures speak of 84,830 soldiers who did not return to the German lines, and who were listed as missing, in addition to 29,690 wounded and frostbitten who managed to return. The losses therefore amounted to 114,520 soldiers out of 230,000. It is difficult to say how many fell in the fighting and how many were captured and sent to prison camps; the fact remains that of the 84,830 missing, only 10,030 returned to Italy after the war.

The defeats of the southern front at Stalingrad and on the Don marked the beginning of the end of Nazi hegemony in Europe. The Red Army continued to advance and liberate the territories that had been occupied by the Germans. Two years later, at the cost of millions of deaths, it arrived in Berlin.

Germany's Allies on the Eastern Front

The Russian front was unquestionably the largest battlefield in all wars fought by man in history: it extended practically without interruption from the Arctic Circle to the Black Sea, for a length that at its peak reached just under 3000 m. kilometres. Such vastness required the use of an enormous quantity of men, especially in the defensive phases of the campaign. The Wehrmacht, already engaged as an occupying force in half of Europe and with a fighting expeditionary force in North Africa, had great difficulty in deploying a sufficient number of men. For this reason, a true multinational force was formed around Germany aimed at recovering men to fight the common Soviet enemy.

This force was extremely heterogeneous, and included both independent states with autonomous expeditionary forces (Romania, Finland, Hungary, Italy, Bulgaria, Slovakia), and foreign volunteers incorporated into the Wehrmacht from the most disparate backgrounds: Latvians, Lithuanians, Estonians, Russians, Ukrainians , Armenians, Cossacks, Walloons, Flemings, Dutch, Croats, even Spaniards and Portuguese, the latter two included in the famous Blue Division of the German army. The origins of these men were as different as the motivations that pushed entire nations or individual volunteers to leave for Russia could be different: the defense of the national territory (Finland) or its liberation from the Soviets (for the Baltic states), calculation political, the obligation to respect an alliance pact, or even to fight Bolshevism as in the case of many Central European and Scandinavian volunteers who enlisted in the Waffen-SS.

Equipment and training also varied greatly, but were generally both far below German standards. In some cases, the most dramatic ones, the contingents of the allied countries were partially or completely re-equipped with weapons and materials supplied by Germany. As regards the volunteers incorporated into the Wehrmacht, the large majority were employed as militarized workers or with garrison duties in the rear, however on several occasions they were organized into autonomous military units with the ranks made up of members of a certain ethnic group and with non-commissioned officers and officers at least partly German. In addition to the aforementioned Spanish division, the Croatian Legion and various other formations incorporated into the German army, many other "ethnic" units made up of Latvians, Estonians, Flemings and Dutch, just to name a few, fought in the Waffen-SS. In all these cases the men were equipped and armed with German material (or war material) and wore distinctive insignia of their origin.

Operation "Barbarossa"

On 22 June 1941 the Wehrmacht attacked Russia on a very broad front. The Red Army was taken by surprise, as was the entire Soviet leadership. The objective of the operation was the conquest of the European part of the USSR with its main cities (especially Moscow) and industrial and mining areas, as well as the destruction of the armed forces which had always been seen as a serious threat to Germany. The attack was conducted by three Army groups (called North, Center, South) for a total of 146 divisions. The Red Army was much larger but poorly organised, deployed and commanded. In the first ten days alone, 40 divisions with 300,000 men and immense quantities of weapons and equipment were wiped out. The quantity of prisoners who fell into German hands was such that in some cases they slowed down the advance towards the east. On September 26, Kiev fell, costing the Russians five armies and one million men, including approximately 600,000 prisoners.

The advance continued unstoppable for months: very serious losses were inflicted and vast territories were conquered. Tiredness and wear and tear, however, began to be felt: the supply lines had stretched out of all proportion and strong contingents had to be left to guard the occupied areas. The rapid advance had in fact left entire regular units of the Soviet army behind the lines: aided by the local population, these had formed dangerous partisan formations that attacked the Wehrmacht from behind. Furthermore, a very cold winter was inexorably approaching and the Red Army was reorganizing and strengthening itself. The German offensive momentum towards Moscow died at the end of 1941, when the Wehrmacht units that had pushed further forward were stopped thirty kilometers from the capital. In the north, however, the advance was stopped in front of Leningrad, while in the south the advance continued for a few more months, finally stopping after the capture of Stalingrad in the autumn of 1942.

The CSIR

Following the invasion of the Soviet Union with Operation Barbarossa, Mussolini decided to send an Italian Expeditionary Force to help his German ally. With this gesture he intended to restore balance to the alliance with Germany after the aid received in Greece and North Africa. Furthermore, he thought that a military commitment would allow for greater advantages at the peace negotiating table, a reasoning similar to that which had brought our country into war the previous year.

The best units available were chosen for the Italian Expeditionary Force in Russia: the Duce did not want to disfigure himself in front of the Fuehrer and had to demonstrate the strength and efficiency of the Royal Army. Of dimensions equivalent to an Army Corps, the CSIR was formed by the "Pasubio" and "Torino" self-transportable infantry divisions and the "Principe Amedeo Duca d'Aosta" rapid division; three divisions in total, plus some units directly reporting to the Command for a total of approximately 62,000 men with 220 artillery pieces, 60 armored vehicles and an air component made up of approximately 85 aircraft. There were 5,500 trucks available and they were enough to transport one division at a time.

The CSIR arrived in Russia by train after a very long journey, and became operational within the German 11th Army in August 1941, first with the Pasubio and then gradually with the other units as they gradually arrived on the line. However, due to the chronic lack of vehicles, some units had to reach the front on foot, as in Napoleon's time.

The Italians made a small but valid contribution to the advance of the Axis forces in southern Russia. Despite limited means, they conquered cities and took prisoners, earning the respect of their allies. The advance stopped at the end of November, with the approach of a very cold winter. The positions conquered were consolidated and the good weather was awaited. In the meantime, the Russians launched some offensives which, however, were stopped, not without some difficulty. Between January and March 1942 the CSIR received some reinforcement units: the "Monte Cervino" Alpine skiers battalion, the 6th Bersaglieri regiment and the 120th artillery regiment, and in June it came under the command of the 14th Army. In August it was renamed XXXV Army Corps and assigned to the ARMIR whose fate it will follow. Up to that point the CSIR had had over 1,600 dead, 5,300 wounded, more than 400 missing and over 3,600 frozen.

Units belonging to the C.S.I.R.

- 30th Army Corps Artillery Group

- Legion CC. NN.Cutting

- CIV Machine Gun Battalion of C. A.

- II Anti-Tank Battalion 47/32

- 1st Motorcycle Bersaglieri Company

- 4th Artillery Engineering Battalion

- 1st and 9th Bridge Engineering Battalion

- VIII Engineer Liaison Battalion

- 1st Chemical Battalion

- 82nd Baggage Department

- 2nd Army Self-Grouping

9th Infantry Division “Pasubio”

- 79th Infantry Regiment

- 80th Infantry Regiment

- 8th Motorized Artillery Regiment

52nd Infantry Division “Turin”

- 81st Infantry Regiment

- 82nd Infantry Regiment

- 52nd Motorized Artillery Regiment

3rd "Celere" Division “Prince Amedeo Duke of Aosta”

- 3rd Bersaglieri Regiment

- Savoy Cavalry Regiment (until 3/15/1942)

- Novara Lancer Regiment (until 3/15/1942)

- 3rd Horse Artillery Regiment (until 3/15/1942)

- 6th Bersaglieri Regiment (starting from 3/15/1942)

- 120th Motorized Artillery Regiment (starting from 3/15/1942)

CSIR AVIATION COMMAND

- 22nd Autonomous Land Fighter Group (of 4 squadrons)

- 61st Autonomous Aerial Observation Group (three squadrons)

- Transport section (on two squadrons)

The ARMIR

In May 1942 Mussolini decided that the Italian contribution in Russia needed to be strengthened. General Messe firmly opposed the idea: he preferred a small but highly mobile, well-equipped and trained expeditionary force to a large army equipped with insufficient and inadequate means. The Duce was adamant: according to his point of view, the ARMIR would have had a completely different weight than the CSIR on the peace negotiation table. Also due to this conflict, Messe did not receive command of the new army, which was assigned to General Italo Gariboldi, but remained in Russia with his CSIR, renamed XXXV Army Corps on the occasion.

The ARMIR, Italian Army in Russia, became operational in July 1942. In addition to the CSIR departments already deployed, it consisted of the Alpine Army Corps with three divisions (Tridentina, Julia and Cuneense) and the II Army Corps with 3 infantry divisions (Sforzesca, Ravenna and Cosseria). Then there were the Vicenza division, the Barbò mounted group and numerous other smaller units directly dependent on the Army command, for a total of approximately 230,000 men with over 20,000 vehicles, 25,000 quadrupeds and 940 cannons.

The first operational actions fell to the Tridentina at the end of August. Precisely in this period the ARMIR was placed under the German Army Group B and was intended for the protection of the left flank of the forces engaged in the battle of Stalingrad. It deployed along the Don basin between the Hungarian 2nd Army to the north and the German 6th Army (replaced at the end of September by the Romanian 3rd Army) to the south. Between 20 August 1942 and 1 September, Soviet troops launched a large-scale offensive against the Hungarian, German and Italian units (who bore the brunt of the attack) deployed in the northern bend of the Don. The offensive was stopped, although with difficulty and suffering serious losses. Above all, the Sforzesca, which was overwhelmed by three enemy divisions, was decimated. On this occasion many units intervened to help the infantry division in difficulty, and the Italian cavalry carried out numerous charges against the Russians, among which that of the Savoy at Ishbuschensky. September and October passed in relative tranquility, with Italian troops deployed to defend a stretch of the front approximately 270 km long.

On November 19, the Russian Red Army launched a massive offensive aimed at encircling the German 6th Army engaged in Stalingrad. The action also led to the annihilation of the 3rd Romanian Army, deployed south-east of the ARMIR. At dawn on 16 December another Soviet offensive (Operation Little Saturn) was unleashed against the lines held by the II Army Corps, which held the central sector of the Italian front. The plan did not take the Italian units by surprise, given that skirmishes and small clashes had been underway along the front since 11 December. The first attack was repelled, but on December 17 the Soviets used their armored troops and aviation, overwhelming the Ravenna lines and forcing it to retreat. The objective of the great Soviet maneuver was to join the two arms of the pincer, made up of powerful armored groups, behind the Italian-German-Romanian deployment. Gariboldi attempted to plug the various gaps by moving departments where necessary, but the retreat without warning of the German 298th division, positioned in the center of the deployment, made the situation even more dramatic. On 21 December the two Russian columns coming from the north and the east met at Degtevo, effectively closing the Italian XXXV Army Corps and the German XXIX Army Corps in an immense pocket.

Almost without means of transport, forced to wander on foot in search of a way out, the ARMIR infantry divisions ended up largely annihilated, decimated by hunger, by a bitter cold, by the attacks of enemy armored columns and partisan units that acted behind them.

For the moment, the Soviet offensive did not involve the Alpine Army Corps, which continued to hold its positions on the Don. The Julia bled itself dry in constant fighting to maintain the front. Meanwhile, the Red Army was preparing for the second phase of the breakthrough: the great Russian river, now covered with resistant ice and therefore also passable for tanks, was no longer the great natural obstacle which until then had so effectively protected the Alpine troops. .

On 12 January 1943 the Soviets launched the second phase of the offensive, overwhelming the 2nd Hungarian Army, deployed to the north of the Alpine Army Corps. The following day they invested the remnants of the Italian infantry deployed together with the German XXIV Army Corps. The Alpine Army Corps remained closed in a pocket which included, in addition to the three Alpine divisions, also the Vicenza division. The order to retreat from the Don was given only on 17 January, very late. Of the 4 divisions only one, the Tridentina, managed to break the encirclement, although heavily bled. Of the other units, only a few thousand men managed to return, mostly stragglers.

With the substantial destruction of the ARMIR, Italian participation in the campaign on the Eastern Front effectively ended. Only a few smaller units remained operational, under the direct control of the Wehrmacht. Between 30 July 1942 and 10 December 1942 the ARMIR had 3,216 dead and missing and 5,734 wounded and frozen. As for the losses during the battle on the Don and the retreat, the official figures speak of 84,830 soldiers who did not return to the German lines, and who were listed as missing, in addition to 29,690 wounded and frostbitten who managed to return. The losses therefore amounted to 114,520 soldiers out of 230,000. It is difficult to say how many fell in the fighting and how many were captured and sent to prison camps; the fact remains that of the 84,830 missing, only 10,030 returned to Italy after the war. In addition to the serious human losses, almost all the armament was left on the field: 97% of the cannons, 76% of the mortars and machine guns, 66% of the individual weapons, 87% of the vehicles and 80% of the of quadrupeds.

The Alpine troops in Russia

The figure of the Alpine soldier is inextricably linked to the Russian campaign. Even if with the CSIR and the ARMIR there were also infantrymen, riflemen, knights, engineers, artillerymen, the figure of the soldier with the felt hat, the pen and the greatcoat covered in snow marching in the boundless steppe has become an icon in the collective imagination.

The first Alpine troops arrived in Russia in February 1942: it was a ski battalion, the Cervino, which was sent as reinforcement to the CSIR. However, the bulk arrived with the Alpine Army Corps, which entered the line together with the ARMIR in July and which counted on a force of around fifty-seven thousand men chosen and trained to operate in mountainous and inaccessible territories. Made up of three divisions, the Tridentina, the Julia, and the Cuneense, the Alpine Army Corps had been created with the idea of using it in the Caucasus mountains. In reality, the only thing that the Alpine troops will find familiar in the steppe is the snow.

The three Alpine divisions were deployed along the banks of the Don, on the left wing of the ARMIR's sector of competence and alongside the 2nd Hungarian Army: they had to maintain a front 70 kilometers long. In autumn we worked hard to strengthen and make the defensive positions as comfortable as possible in anticipation of the imminent arrival of winter. The works were excellent for keeping the men busy, but the works carried out proved to be of little use: on 15 December the Soviets broke through elsewhere and surrounded the Italians. Initially the Alpine troops held their positions, driving back the attackers from every direction who attacked, then, having received the order to fall back to avoid annihilation, after a month of fierce fighting on 15 January 1943 they began the retreat. At this point only the Tridentina remained efficient and able to fight. The remains of the Cuneense and the Julia remained behind and on 27 January they were almost totally captured together with what remained of the Vicenza division at Waluiki. The Tridentina, however, managed to break through the pocket at Nikolajewka, albeit with very serious losses.

After a 200 kilometer march in the snow that lasted 15 days and was punctuated by countless battles, the survivors finally reached the friendly lines. On January 31st the remnants of the Alpine Army Corps arrived in Schebekino. The seriously injured were sent to various hospitals, some were loaded onto a hospital train for repatriation. The men still able to do so set off again and arrived in Gomel on March 1st, after a long march in the snow and at temperatures constantly below zero. Of the 57,000 Alpine troops who had left, only 11,000 returned to Italy: 6,400 were from Tridentina, 3,300 from Julia and 1,300 from Cuneense.

THE ALPINE DEPARTMENTS THAT OPERATED IN RUSSIA

Subordinate to the Army Command:

- Alpine Skiing Battalion “Monte Cervino”

Subordinated to the Alpine Army Corps:

- 2nd Alpine Division “Tridentina”

- 5th Alpine Regiment

- Morbegno Battalion

- Tirano Battalion

- Edolo Battalion

- 6th Alpine Regiment

- Vestone Battalion

- Val Chiese Battalion

- Verona Battalion

- 2nd Alpine Artillery Regiment

- Bergamo Group

- Vicenza Group

- Val Camonica Group

- 3rd Alpine Division “Julia”

- 8th Alpine Regiment

- Tolmezzo Battalion

- Gemona Battalion

- Cividale Battalion

- 9th Alpine Regiment

- Vicenza Battalion

- L'Aquila Battalion

- Val Cismon Battalion

- 3rd Alpine Artillery Regiment

- Conegliano Group

- Udine Group

- Val Piave Group

- 4th Alpine Division “Cuneense”

- 1st Alpine Regiment

- Ceva Battalion

- Pieve di Teco Battalion

- Mondovì Battalion

- 2nd Alpine Regiment

- Borgo San Dalmazzo Battalion

- Dronero Battalion

- Saluzzo Battalion

- 4th Alpine Artillery Regiment

- Pinerolo Group

- Mondovì Group

- Val Po Group

The Russian Red Army

In 1941, there were approximately 25 million Soviet citizens eligible for compulsory military service. The draft lasted two years and the training was very approximate. Initially the regular army included around 9 million men, almost half of whom were deployed in the western part of the USSR. Operation Barbarossa surprised the Red Army in the midst of its reorganization, after the serious shortcomings that came to light during the Winter War against Finland.

The attack caught the Soviet army totally unprepared: in a few months it suffered devastating losses, in the order of millions of men dead or prisoners. While the Wehrmacht was in full advance, a General Staff (Stavka) was created under the direct control of Stalin. The Stavka placed the military districts under centralized political control and was able to organize the exploitation of national resources extremely effectively; however its main function was to coordinate all forces in the Soviet Union. At the same time, strategic reserves began to be set aside for counterattacks to be launched as soon as the opportunity arose.

In 1941 the Soviet army was organized into armies made up of around 12 divisions, for a total that could exceed 200,000 men; subsequently, to make them more manageable, their size was reduced to 8 divisions. As the war progressed, the Red Army grew larger and larger, so much so that in 1944 there were 48 armies deployed from the Baltic to the Black Sea. The large basic unit of the Red Army was the rifle division. After the harsh lessons of the beginning, its dimensions were reduced, but its firepower was increased: the supply of mortars and cannons were increased, but above all, as many as 2000 men were equipped with machine guns, very effective in close combat. The "spearhead" was made up of the armored troops, which starting from 1943 were grouped into armies. Even the artillery, apart from the divisional units which had little value, was concentrated in specialized divisions.

Unlike the majority of armies that fought in World War II, Italy had not foreseen the replacement system. The unit that suffered losses in battle did not receive reinforcements from the rear but continued to fight until total annihilation or until it was withdrawn from the front to be disbanded or reconstituted. The recruits formed new divisions that were sent to the front in full ranks. The result of this policy is that a name division, if in line for a long time, could have great experience but the strength of a regiment or even less.

Another characteristic of the Red Army was the presence of "Guard" units: this was an honorific title granted to those units that had particularly distinguished themselves in the field. In practice these were elite units, which as such also received better equipment. The efficiency rating of a Guards division was considered equal to that of a German infantry division.

The supply service was rather poor, and there was a chronic lack of motor vehicles. This problem was partly overcome by Anglo-American aid, which contributed half a million motor vehicles starting from 1943.

It has been estimated that 13,700,000 Soviet soldiers died during World War II.